In The Myth of Normal, Dr. Gabor Maté explores one of the most challenging and often overlooked truths in modern medicine: our minds and bodies are not separate systems but deeply interconnected ones.

Psychological factors—especially trauma—can profoundly influence physical health, contributing to the development and progression of serious illness. Far from being abstract or speculative, this connection is supported by decades of research showing that emotional states and life histories leave biological marks that manifest as disease.

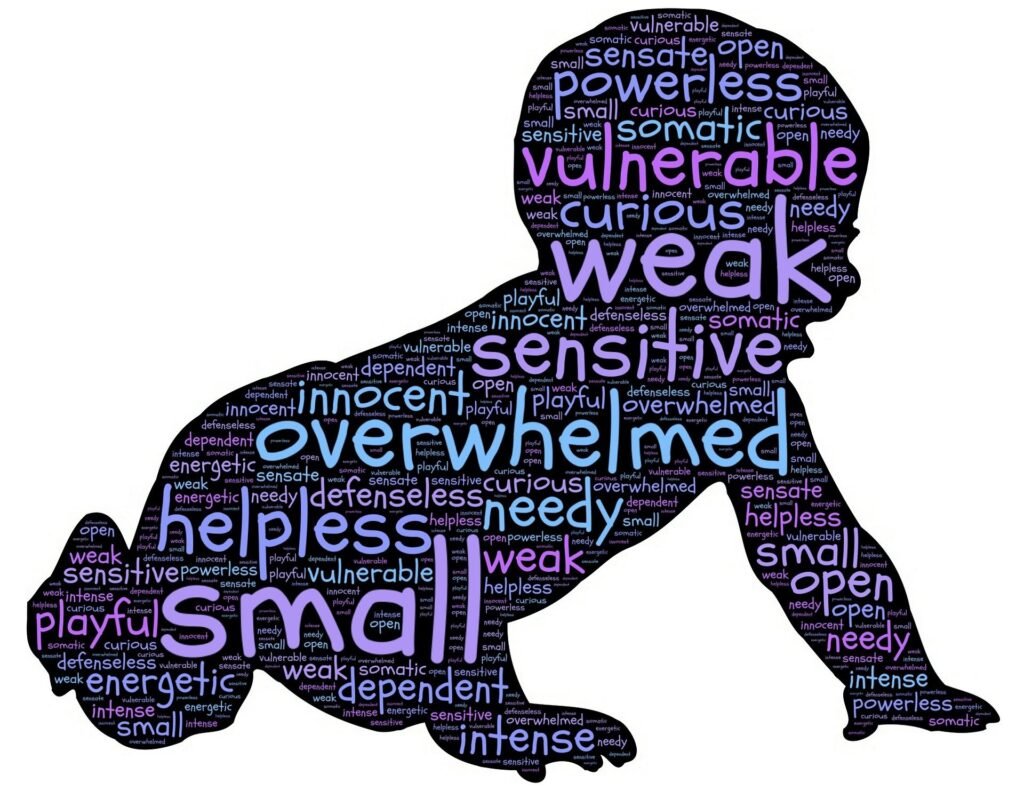

At the core of Maté’s argument is the idea that untended emotional pain doesn’t disappear—it becomes embodied.

Many studies provide compelling empirical evidence that patterns of trauma, stress, emotional suppression, and unresolved inner conflict correlate with increased susceptibility to major illnesses, including cancer and cardiovascular disease.

One early study from Germany in 1982 illustrates this vividly. Researchers interviewed 56 women awaiting breast biopsies, asking about emotional suppression, avoidance of conflict, altruism, self-sufficiency, and difficulty asking for help. What they found was striking: both the interviewers and a group of independent “blind” raters—who had never met the women—could predict with high accuracy whether a woman would be diagnosed with cancer based solely on the psychological themes in her responses. Women whose answers showed suppressed feelings, conflict avoidance, and a tendency to put others before themselves were far more likely to have cancer. This study suggests that the emotional life of a person is embedded in their physical outcomes.

In a broader review of research on anger and cancer, Professor Sandra Thomas found a consistent pattern: cancer patients often reported extremely low levels of expressed anger, hinting at anger suppression, whereas those who were able to engage with their anger—mobilizing it rather than repressing it—showed tendencies toward more vigorous coping. In other words, how people relate to their emotions may influence their disease trajectory.

Beyond cancer, the mind’s influence extends clearly to the cardiovascular system. A 10-year prospective study of over 22,000 women by Natalie Slopen and colleagues found that high job strain significantly elevated the risk of cardiovascular events. Women experiencing high levels of stress at work were nearly 40% more likely to suffer a heart attack or other heart condition than women with low job strain. Chronic stress, it seems, takes a cumulative toll on the body.

The impact of psychological trauma on the heart does not stop with adult stressors. A large population-based study in Canada linked childhood sexual abuse to dramatically increased odds of heart attack later in life. Men who reported childhood sexual abuse had nearly three times the likelihood of experiencing a myocardial infarction compared with non-abused men. This finding underscores a critical point: early life trauma can leave a biological imprint that increases vulnerability to serious disease decades later.

Finally, research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II found that women with high levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms had double the risk of developing ovarian cancer compared to women with no trauma exposure. Even when controlling for other factors, PTSD emerged as a powerful predictor of cancer risk, reinforcing the idea that psychological trauma doesn’t just influence mood or behavior—it alters physiology in ways that can predispose the body to illness.

Taken together, these studies challenge the conventional medical assumption that physical disease is merely the result of genetics, pathogens, or lifestyle choices in isolation. Instead, they point to a deeply embedded link between emotional experience and biological reality. Dr. Maté frames this not as a moral judgment but as a call to attend to the emotional dimensions of human life with the same rigor and care that we bring to physical symptoms.

The body remembers what the mind tries to forget.

Understanding this truth opens a pathway not only for better medical treatment but for more compassionate models of care—ones that recognize psychological well-being as foundational to physical health.